Matching For Color, Grain Pattern, and Figure

Table and dresser tops, bed headboards, and large panels are almost always made up of two or more boards. If the boards match well for color, grain pattern and figure, one's eye takes in the craftsmanship, style, and beauty of the item of furniture, and how the various components relate to each other and the entire item. The observer develops appreciation and respect for the item. Hopefully the owner develops an emotional bond with the item - the longer it is kept the more money the owner saves and fewer trees are cut for replacement furniture. Ideally it becomes a family heirloom, helping to hold and trigger treasured family memories.

If the boards match poorly, one's eye is drawn away from the overall item and to the joint itself. If one or more of color, grain pattern and figure actually clash where the boards meet, one's attention can be drawn more to the disappointing joint and less to the overall item. Increased attention to the disappointing joint can grow to become dissatisfaction and lack of respect for an item of furniture that might otherwise meet the needs of the owner. Eventually the dissatisfaction results in premature replacement of the item, an unnecessary additional expense.

For communication purposes, some definitions might be helpful. In the following paragraphs, a board will refer to a full length piece directly from a sawmill. A board-cut will be a piece from a full length board. Finally, an edge joint will be the meeting of adjacent board-cuts.

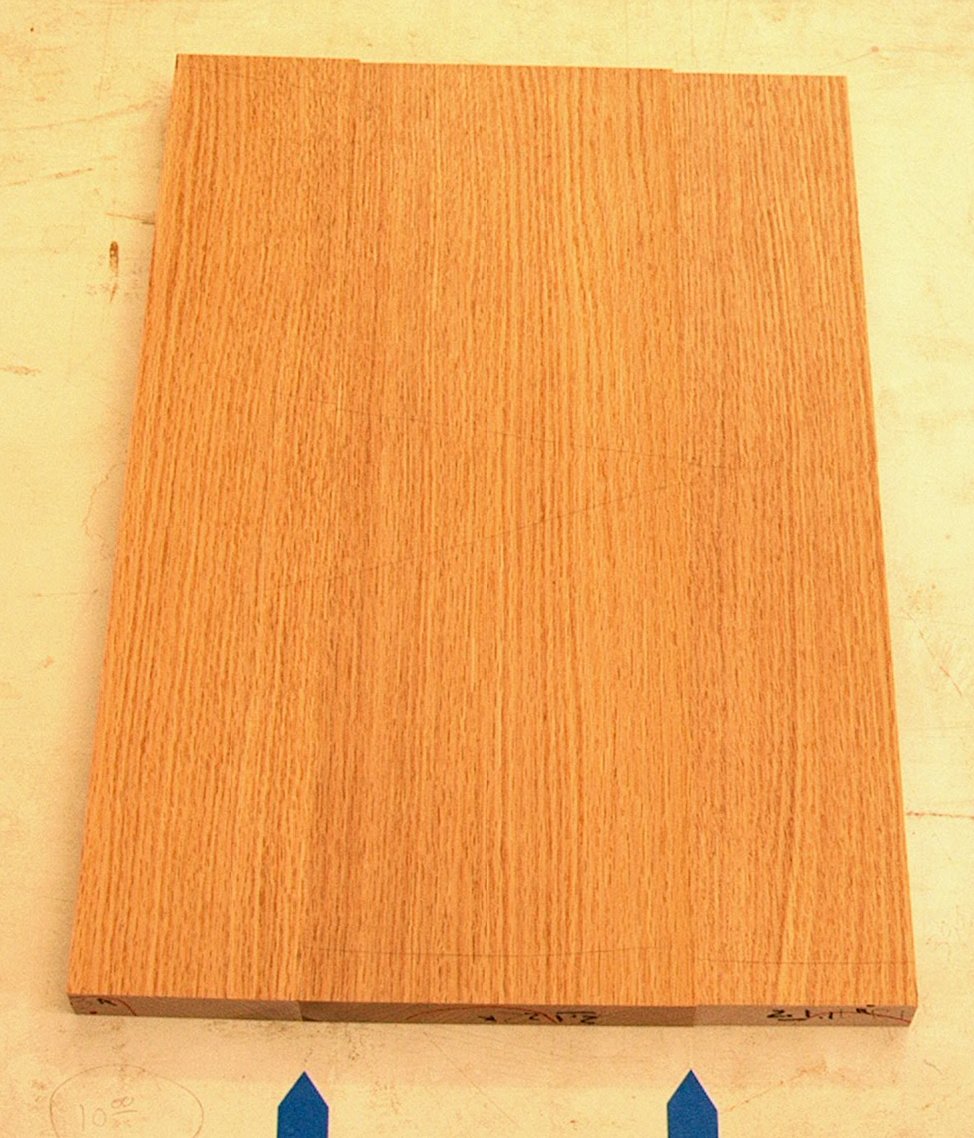

This picture shows three boards that will be glued to make a drawer front. The blue arrows show the edge joints. The matches are very good, so one's eye will be drawn to the drawer front as it relates to the overall desk, rather than a clashing edge joint.

This picture of a table in a consignment shop shows very different grain patterns in adjoining boards. It's hard to imagine a person appreciating the tabletop and enjoying time spent at the table. Perhaps that explains why the the table looks almost new.

In a perfect world, all board matches would appear seamless. But wood is never perfect. An important but often ignored traditional woodworking practice is to study options and select for the best possible matches between board-cuts.

A initial step for board matching is to trim edges that are damaged or contain sapwood. Sapwood is strong enough to be used in furniture, but should only be used artistically. In this picture, the factory simply didn't bother to trim the edge back to heartwood. The gratuitous sapwood draws the eye from admiring the lines of the table to an obvious edge joint. One has to try to overlook the sapwood in order to appreciate the table. The owner apparently was not able to overlook the sapwood, as this second-hand store table looks almost new.

For special projects one can try to order from a "flitch-log" - the boards are kept together as the log is sawn. There will be a premium charge when such boards are available. The grain pattern on adjoining faces of consecutive boards will be very similar.

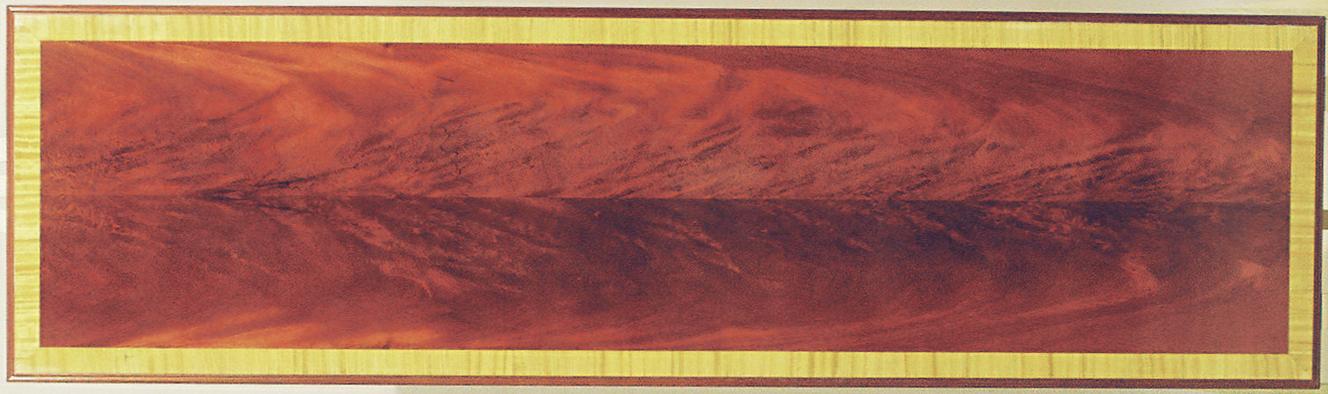

The center of this tabletop was made using veneer rather than solid wood, but the two sides of the center edge joint are consecutive leaves of veneer, similar to consecutive boards from a flitch-log. The grain patterns of the two sides are mirror images at the center seam because the top surface of the second leaf of veneer is abutting the bottom surface of the first leaf, what is known as a book match.

Veneer is sliced by a sharp blade, and there is no sawdust or lost wood. Color, grain pattern and figure match perfectly between the bottom surface of one leaf and the top surface of the next leaf. Sawing boards from a log creates sawdust, wood that is lost. Sawing logs at a mill and flattening and straightening the resulting boards in the workshop can result in as much as 1/2" or more of wood lost between boards. Color, grain pattern and figure evolve through wood, so the match at an edge joint between consecutive flitch-log boards will never be as good as a match using consecutive leaves of veneer. After all, that half inch lost between consecutive surfaced flitch-log boards would have made twenty leaves of veneer.

For small door and other prominent panels, one can "re-saw" on the bandsaw a relatively thick piece of wood into two thinner pieces. For example, a piece 12" long, 4" wide, and 1" thick could be re-sawn into two pieces each 12" long, 4" wide, and 1/2" thick. If the starting piece did not have significant internal stresses, the resulting two pieces will be relatively flat. After flattening and straightening, perhaps only 3/16"" of wood between the resulting two pieces would be lost. They could then be bookmatch edge glued to make one panel 12" long and 8" wide with a pretty good grain pattern reflection for a pleasing visual statement.

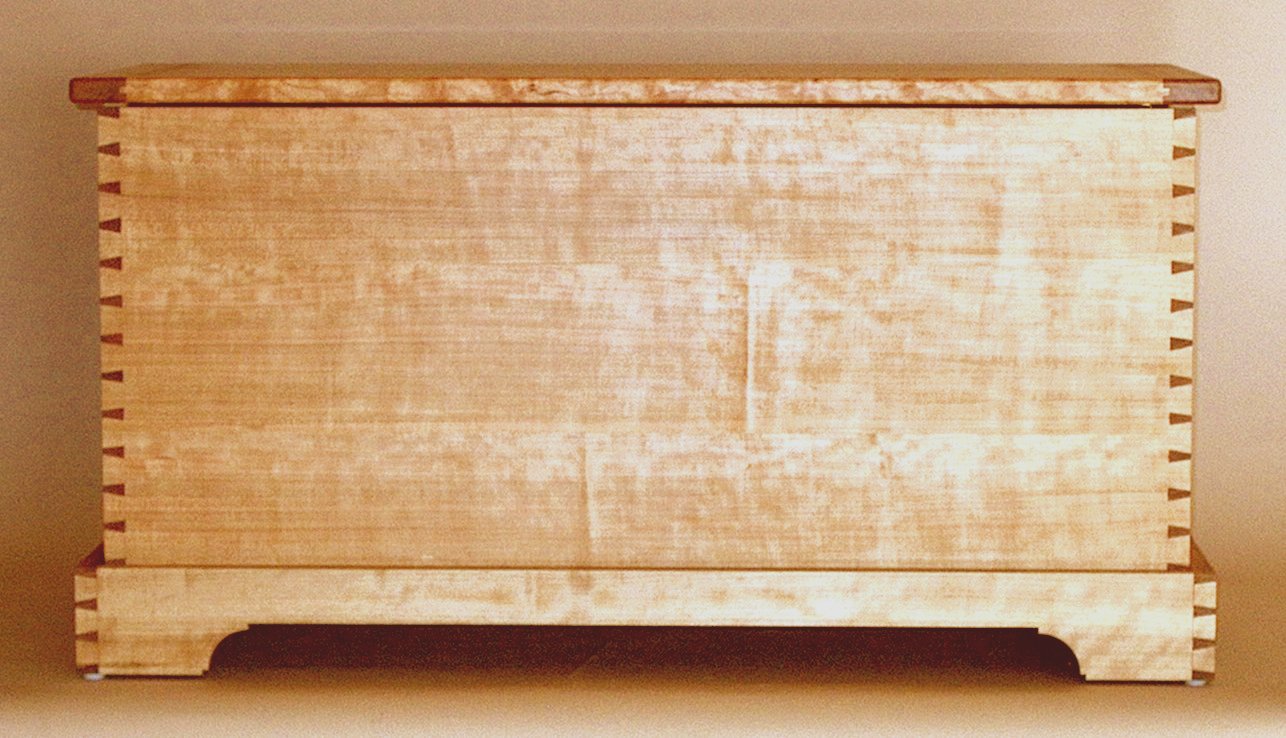

After consecutive flitch-log boards, the next best situation is where all the board-cuts for a glue-up can be taken from the same board. The front side of this cherry blanket chest consists of three pieces from one board. After aligning the edges of each piece to its grain pattern, the resulting matches were very good.

One's attention is drawn to the proportions of the chest; relationship of top, front and base; and the hand cut dovetails; not to edge joints.

(For more information on trimming the edges of board-cuts to improve matches, see "Aligning The Edges of a Board to the Grain Pattern.")

Often board-cuts from different boards have to be used, as in the top of the blanket chest. The color, grain pattern and figure of wood can be previewed by wetting the pieces with liquid. Water is slow to evaporate, and can raise grain - mineral spirits, naptha, and lacquer thinner all are more commonly used. Wipe the wood thoroughly to see how the surfaces will look after finishing, and then evaluate for color, grain pattern and figure. There were perhaps eight or ten boards and board-cuts that were available for the chest top, and the best were selected. Additional time was needed to evaluate the order of the four for the field and the two for the breadboard ends, and which surface was used for each. But the extra effort resulted in a much better top. Rather than being distracted by edge joints, one's eye is drawn to the mesmerizing figure and elegant breadboard ends.

In both these examples, the matches were aided by consistent grain pattern. The boards ordered for the blanket chest were all quartersawn. But there were variations in grain pattern even between the quartersawn boards. On a few, the grain pattern curved along the length of the board, or even meandered from side to side.

Less desirable grain patterns can be used where they won't show, such as the bottom of a chest or the interior framework of a desk, and for testing set-ups such as for mortise and tenon joints or practicing dovetails.

(For more information on grain patterns, see "Common Board Grain Patterns.")

A characteristic of some woods that can complicate matching is chatoyance. Some woods appear lighter or darker depending whether they are viewed from the left or right, from the front or back. From the perspective of this photo, there appears to be a less than ideal match between the second board and those on each side. But viewed from a slightly different angle the matches are very good. The mahogany veneer tabletop at the top of this page also exhibits chatoyance at the right end.

If always viewed from the same angle, with the same light source, chatoyance can make a piece look unplanned. But seen from a moving perspective, such as walking past the piece, chatoyance can make a piece dramatic as the wood seems to move or shimmer.

Quatersawn lumber has an elegant grain pattern, but the vast majority of logs are flatsawn. This methodology is easier for the sawmill, but the resulting "arches and cathedrals" grain patterns are stronger, with more variation between boards.

(For more information on grain patterns, see "Common Board Grain Patterns.")

This tilt-top table is designed in the style of a French Provincial vineyard table from the 1800's. As such, it was felt that flatsawn boards would be more appropriate for the top than quartersawn.

Each of the five boards show arches and cathedrals, but they are distinctly different in each. The synonym for this grain pattern, "ovals and ellipses," is more apparent in the top and fourth boards.

As one can easily expect, board matching is more difficult with flatsawn lumber. Because of the log sawing methodology, the grain pattern is centered on only half the boards, and the width of the boards varies greatly.

More than an hour was devoted to evaluating board order and placement, trimming edges of some of the boards to shift the grain pattern laterally and/or align the pattern to the edge of the board. But in the resulting tabletop the edge joints are indistinguishable and the eye takes in the oval shape and the rustic grain patterns.

The foot rail on this bed shows poorly planned use of a flatsawn board. The grain pattern is falling off the bottom of the rail, and the arches all are at the left end. It suggests the factory was not concerned with the aesthetics of grain pattern. It's hard to feel good about owning this bed frame.

Board matching is too often overlooked at the beginning of furniture construction. It can have a tremendous impact on the desirability of the finished piece.

Return to Best Traditional Woodworking Practices page

Appointments are suggested for your convenience.